Step-by-step guide for creating, testing, and using external subsystems#

How to plan for your subsystem integration#

You need to determine if your subsystem has a pre-mission aspect, a mission aspect, post-mission aspect, or any combination of these. For example, if you are sizing a part of the aircraft, you might only need the pre-mission systems. But if you’re trying to track the performance of a dynamic variable – something that varies across the mission – you’d want to add a mission system. The most common and general subsystems have both pre-mission and mission systems.

The external subsystem interface allows you to provide OpenMDAO Systems (Groups or Components) for the pre-mission, mission, and post-mission parts of Aviary. You’ll want to consider which parts of your model should live where.

It helps to diagram your model and break it down into pre-mission, mission, and post-mission systems that you’ll need.

I find XDSM diagrams very helpful for doing this as they have prescribed and clear formats that you can easily share with others.

See this video for more information on understanding and creating XDSM diagrams.

Specifically think about the inputs and outputs to each one of these systems and what needs to be exposed to Aviary.

For

missionsystems, these would include anything that occurs during the flight of the aircraft. Thus, if you have n nodal mission analysis points, this system would be analyzed n times per mission. An example of mission systems include batteries, propulsion, sensors, thermal systems, and anything that varies in time.pre-missionsystems include anything that happens before a mission is analyzed. This includes weights, structures, geometry, other one-time-per-optimization iteration analyses.pre-missionalso includes anything associated with pre-flight systems. For example, if your takeoff analysis is analytic instead of mission-based, it would live here.post-missionsystems are evaluated after the mission is analyzed. This is useful for anything that needs the mission timeseries information, including acoustics, emissions, costs, etc.

Define variables for Aviary to use#

Next up, define the variables that you will need for your model. You can use any sort of variables internally within your model, but if you want Aviary to know about the variables you must define them in a specific way. Specifically, if you use the Aviary naming convention of 'aircraft:...' or 'mission:...' and promote them out of your system, then other Aviary subsystems can see and use those values.

If your subsystem does not need to tell Aviary about any new variables (i.e. all of the variables that your system will use within Aviary already exist in Aviary itself), then you can skip this step. You will not need to add any variable or metadata info.

First, view the battery_variables.py file to see an example of the variable hierarchy we use in Aviary. You can also look at the core Aviary variables to see what’s available already. You can add any arbitrary system as a subclass within here. Items that define aircraft properties should go within

Aircraftwhereas any variables pertaining to theMissionshould exist there.These variable names are what’s used within the OpenMDAO system that Aviary uses. This sort of hierarchy is a purposeful design choice to make it clear what values live where, which subsystem they belong to, and that they are named the same between different systems. Additionally, we recommend including the legacy name of any variable you add that so that users of your builder will know how the variable names map to existing analyses.

Now, with the variable names defined, we need to define variable metadata. Variable metadata helps Aviary understand your system. It also helps humans understand what units, defaults, and other values your variables use. Check out the battery metadata example as well as the core Aviary metadata.

When you define your variable metadata, you’ll use the same names you just defined. With those names, you’ll provide units, a brief description, and default values. You’re not locking yourself into specific units here, but by providing units then Aviary can convert the values behind-the-scenes to whatever units are actually used in the code. Users can input variables in any units that can be converted to those units prescribed in the metadata.

Making OpenMDAO groups for your subsystem#

Once you’ve diagramed your model and defined your variables, create OpenMDAO Groups for each of the systems you need. Some disciplinary models may only need pre-mission systems, whereas others may need a different subset of these three possible systems. If you’re using a tool that already provides models in the OpenMDAO framework, you won’t have much (if any!) work to do here.

If you haven’t yet used OpenMDAO, definitely dig into its docs or talk to somebody who has worked with it. These groups will be what Aviary adds to its own model.

To use gradient-based optimization in an efficient way, it greatly benefits you to provide derivatives for your model. It’s not strictly necessary, but the core Aviary tool has efficient derivative computations throughout. To take full computational advantage of this, your OpenMDAO models should also compute derivatives.

Using the SubsystemBuilder class#

Now we’ll create your subsystem builder. This is arguably the most important step since it exposes your model to Aviary using a consistent interface. The main idea surrounding the subsystem builder is that subject matter experts (you!) will create a specialized Python class that defines specific methods needed by Aviary to integrate your subsystem. I’ll walk you through this process now, but don’t worry – we also have some tests to help ensure your subsystem builder is set up correctly.

First, let’s work out some ground rules of the subsystem builder. You’ll inherit from

SubsystemBuilderwhen you create your builder. This base class features all methods used by Aviary, even if your specific subsystem doesn’t need them (this varies on a subsystem to subsystem basis).Most all of these methods are documented in-line, as well as on the doc page. I hope that you can follow those and understand what to do with your model, but if you can’t, please let us know your questions and we’ll rework these docs.

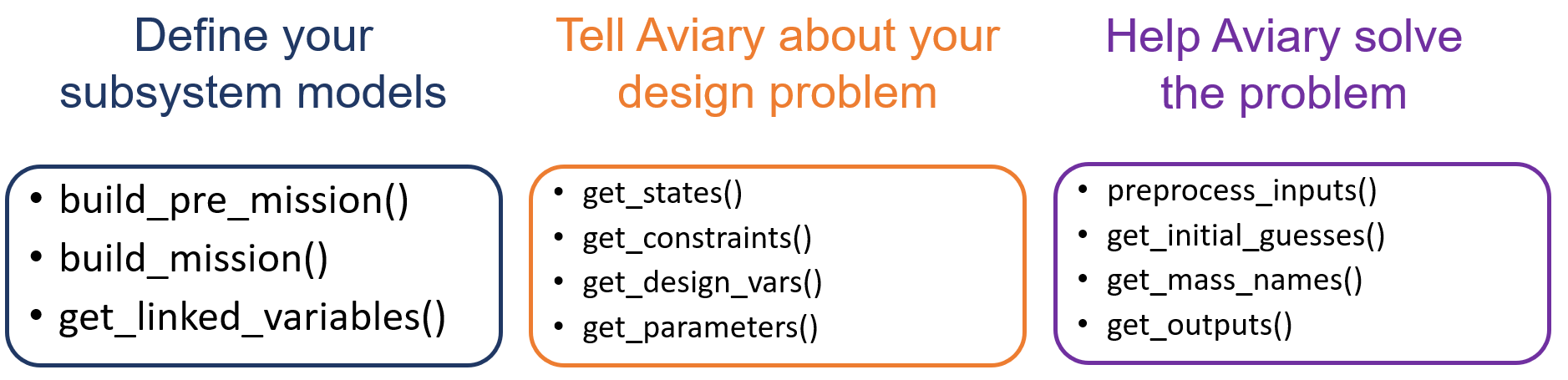

These methods can be roughly divided into three broad categories (shown in the graphic below):

Defining your subsystem

Telling Aviary about your design problem

Helping Aviary handle your subsystem

Each one of these categories is only a notional way of organizing the methods, but I find it helpful to explain their general purposes.

To integrate external subsystems into Aviary, you need to use the SubsystemBuilder class as a template for creating your builder object.

This class provides you with skeletal methods that you replace to specify the behavior of your subsystem.

The methods you should implement depend on what type of subsystem you’re building.

Testing your builder and ensuring it’s behaving as intended#

Okay, now we should test your subsystem builder to make sure it’s providing the correct outputs to Aviary. You don’t have to put it into Aviary (yet!) to do this. Look at the test_battery_builder.py file to see how to test your subsystem. This is also detailed in the battery subsystem example doc page.

If everything goes well then those tests passed. If they didn’t, you should get some info about your builder that you can use to fix any bugs or errors.

This test probably won’t catch everything that could go wrong when interfacing your model with Aviary, but hopefully it catches the basic problems. If you reach an error that the test doesn’t help you with or it’s not clear what you need to do to fix your builder, please let us know!

Those additional 'external_subsystems' entires are where you add your subsystem instances. Let’s go through that step-by-step now.

Add the

external_subsystemslist to your mission phases. For each disciplinary subsystem you’re adding, add them to theexternal_subsystemslist. Each phase has its ownexternal_subsystemslist and this is on purpose. You may only care about your subsystem within a particular portion of the aircraft flight, or maybe you care about your subsystem throughout the entire flight. By defining the external subsystems on a phase-by-phase basis, you have exquisite control over where they’re added to Aviary. This is especially helpful for more computationally expensive subsystems.Add any

external_subsystemsto your pre- and post-mission phases too. If you have pre- or post-mission analyses in your subsystem, make sure to add theexternal_subsystemslist to thepre_missionandpost_missionsub-dicts within thephase_infodict. This means that Aviary will build and use those systems before or after the mission; otherwise Aviary won’t know to put the systems there.Start with a simple mission in Aviary. To begin, try adapting the

run_cruise.pyscript to use your subsystem. Replace theBatteryBuilder()instance with your subsystem, for example. You might need other setup or inputs based on the complexity of your model. But in general, it helps to start with the simplest mission you can. In this case, that’s probably a steady level cruise flight.Even though this is a “simple” mission, there’s still a lot that can go wrong. It turns out that designing an aircraft is challenging sometimes. I don’t expect your mission optimization to converge well your first try; it often takes some debugging and digging to get your subsystem integrated well. It’s really challenging to write docs to help you do this without knowing more about your system, what it’s trying to do while the aircraft is flying, and what you’ve already checked. That being said, make sure to reach out if you’re encountering problems here.

Move on to a multi-phase mission. If you’re able to get a cruise-only mission converging well with your subsystem, next we should move on to a multiphase mission that features takeoff, climb, cruise, descent, and landing. This is much more representative of true aircraft performance (obviously) and generally puts your subsystem model to the test. This also introduces the idea of linking variables between mission phases, which introduces additional complexity to the model. For instance, your battery’s charge at the end of climb needs to match the battery’s charge at the beginning of cruise. Details like this can be tricky depending on your subsystem, so again this step often involves some debugging.